On 4 October, 2023, India lost one of its most remarkable, consequential and pioneering conservationists at the age of 94. Anne Wright (born Nora Anne Layard), the daughter of a British civil servant, not only decided to adopt India as “her country” while her parents and younger sister left following Independence but also worked tirelessly for decades to protect its fauna.

From breaking the gender barrier in the world of wildlife conservation to playing an instrumental role in the drafting legislation that governs wildlife protection in India today, and personally pushing through the creation of a number of Protected Areas while working closely with local communities and bureaucracies, Anne was a changemaker in the truest sense.

It’s an awe-inspiring story of advocacy, commitment, compassion, and perseverance. Suffice it to say, it’s impossible to capture Anne’s work entirely given its immense scope and breadth. However, it’s possible to capture some of its fascinating highlights with assistance from wildlife historian Raza Kazmi, who knew Anne and her family well.

A woman of the forests

Born in 1929, Anne spent a lot of her childhood in the forests of what are today the tiger reserves of Melghat and Kanha in the erstwhile Central Provinces. After all her father was an officer with the erstwhile Indian Civil Service (ICS) serving in the Central Provinces that include parts of present-day Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Maharashtra.

According to this 2013 tribute written by the Sanctuary Nature Foundation, “As a child, she [Anne Wright] would search for scorpions, follow tigers’ pugmarks on golf courses and watch panthers leap across the parapets of Amravati’s rugged Gawilgarh Fort.”

Despite her fascination with wildlife, Anne lived at a time when big game hunting was still commonplace. Speaking to The Better India, wildlife historian Raza Kazmi says, “Anne Wright and her husband Robert Hamilton Wright (Bob Wright to those who knew him) had begun coming to the forests of Palamau (in present-day Jharkhand) from about 1949–50 onwards.”

“In those days, as was the norm, most of Bob’s friends liked doing a bit of hunting and the forests of Palamau were a favourite among hunters based in Calcutta (Kolkata). Moreover, the British conglomerate Bob was working for at the time in Calcutta, Andrew Yule & Co Ltd, had one of its major supply sites in Palamau. Anne, who had started living with her husband in Calcutta by then, would come along with Bob often. She never hunted but used these visits to get to know these forests of Palamau quite intimately over the next few years,” adds Raza.

Anne always carried a deep love and admiration for India’s forests and wildlife. But it was only in the mid-1960s when conservation really became a part of her life following regular visits to the jungles of present-day Bihar and Jharkhand, and particularly after the onset of the Great Bihar Famine of 1966–67 which took a massive toll on the local wildlife.

Saving Palamau

From 1949–50 onwards, Anne’s family would regularly visit the forests of Palamau (known for its tigers) located in the Latehar district (formerly part of Palamau district) of present-day Jharkhand. According to Raza, “While Anne had always been a forest and wildlife enthusiast, given her childhood spent in the wilds of Central Provinces with her father, she told me that it was the naturalist EP Gee (credited with the discovery of the Gee golden langur) who was instrumental in guiding her towards a life of wildlife conservation.”

“By the 1960s, Anne had begun noticing a decline in wildlife in Palamau and began actively trying to do her bit to address it. Over the years she had cultivated friendship with a lot of committed and like-minded forest officers of undivided Bihar among whom SP Shahi was the most prominent. When the 1967 Great Famine of Bihar hit Palamau, Anne dropped everything, collected funds from various donors, and came to Palamau to do her bit to help out both the affected communities and the wildlife that was perishing during this crisis as well,” he adds.

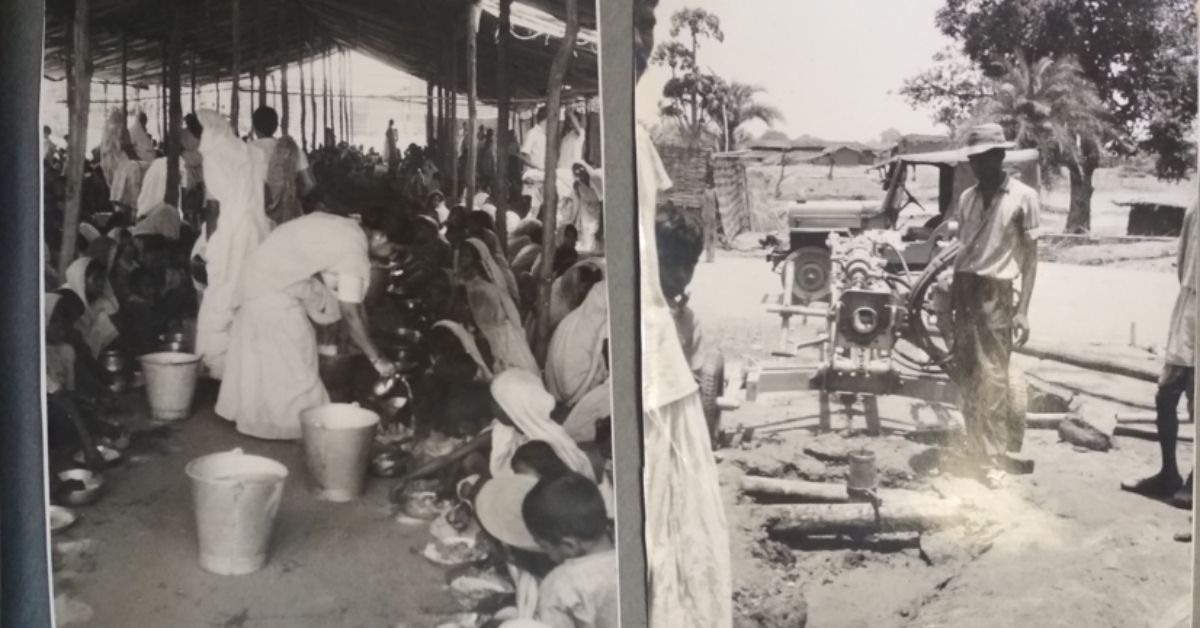

Anne spent months in remote forest bungalows in the forests of Palamau and worked tirelessly to organise communal meals and water supply for the people. She also developed waterholes for the bewildered wildlife that was coming out of the forests in search of water and getting killed in the process.

“Her fortitude and toughness earned her the respect of the forest bureaucracy and her kindness touched many of the local Adivasi communities who in most cases completely relied on the food, water and medicines provided by Anne’s team for relief,” notes Raza.

However, she had begun realising that the forests and wildlife of Palamau could not be protected in the long run with just individual efforts. She also knew that it would need an institutional support system both within and outside the government to make meaningful long-term change. According to Raza, those were the days when funds were severely lacking for the forest department with almost nothing for the management of wildlife or their protection.

“So, she started working on both fronts for Palamau. She worked tirelessly in convincing and lobbying the political class at the State and Union government levels on the importance of Palamau and the preservation of its wildlife. Simultaneously, she helped set up the India chapter of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in 1969 and ensured that Palamau was among the first forests that the organisation focused its energies upon,” explains Raza.

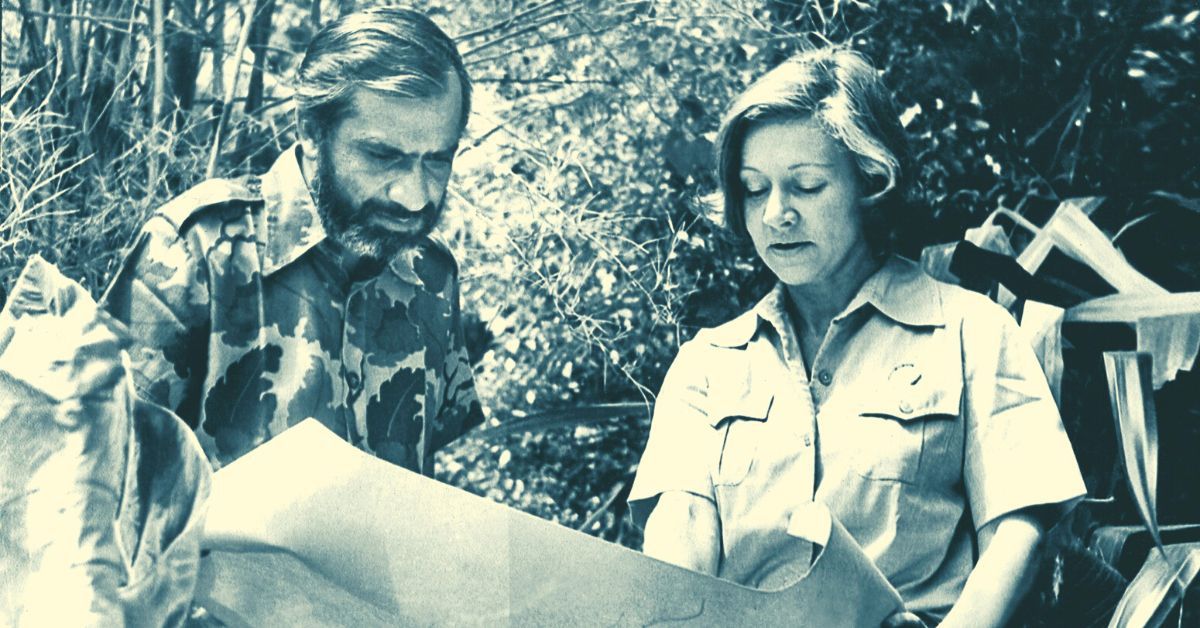

He adds that she began helping the forest department itself with making a case for this forest from within the system. Anne brought top ecologists and experts from IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) and WWF — such as Dr Colin Holloway — to visit Palamau. She got them to train the officers and staff there in the latest techniques of wildlife management, while also helping them draw a wildlife management plan for this region.

“In fact, Anne spent long hours with Dr Holloway, SP Shahi and other forest officers like RP Singh and JP Sinha in devising the first comprehensive wildlife management plan in India’s history for a ‘Game Sanctuary’. Such a plan was almost unheard of in the pre-Wildlife (Protection) Act era,” he says.

Before the introduction of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, a wildlife-rich forest was sometimes notified as a ‘Game Sanctuary’.

Meanwhile, Anne also helped in advising the forest officers in Palamau with creating the necessary infrastructure for the management and conservation of wildlife in the region, and also ensuring that the funds-starved offices of Palamau Forest Division (under which these forests lay) got funding from non-governmental sources and donors, “the biggest of which was WWF where she had considerable say and influence,” adds Raza.

While she was doing all this groundwork while being in the field at Palamau, she was simultaneously pushing for Palamau’s protection at the Union Government level as well.

From Palamau to Project Tiger

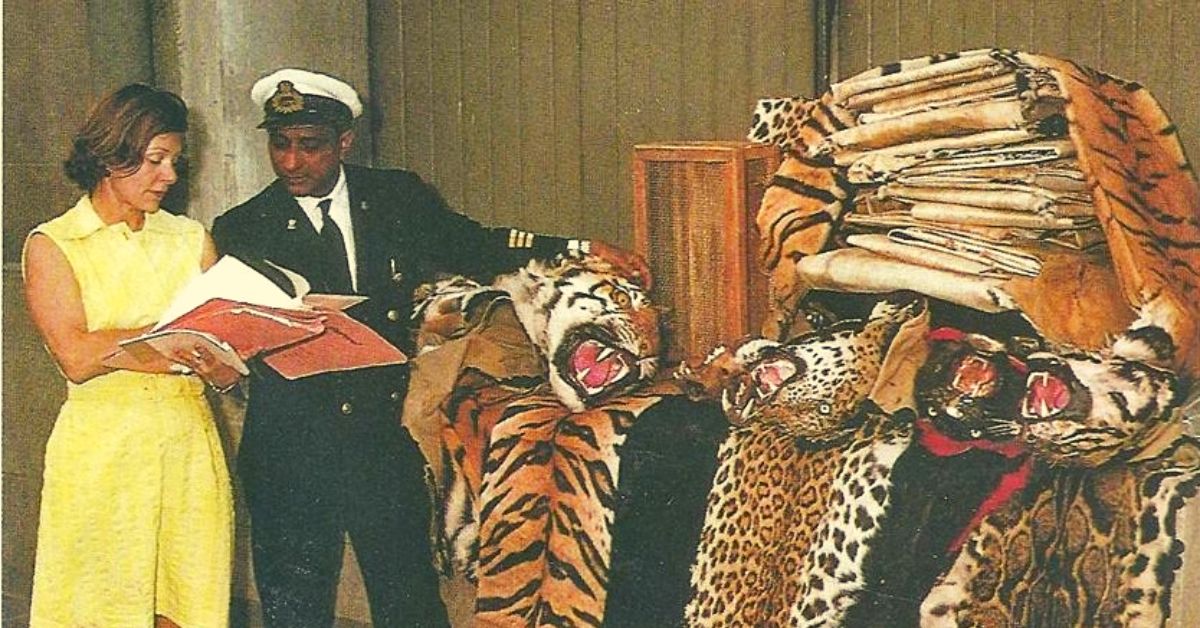

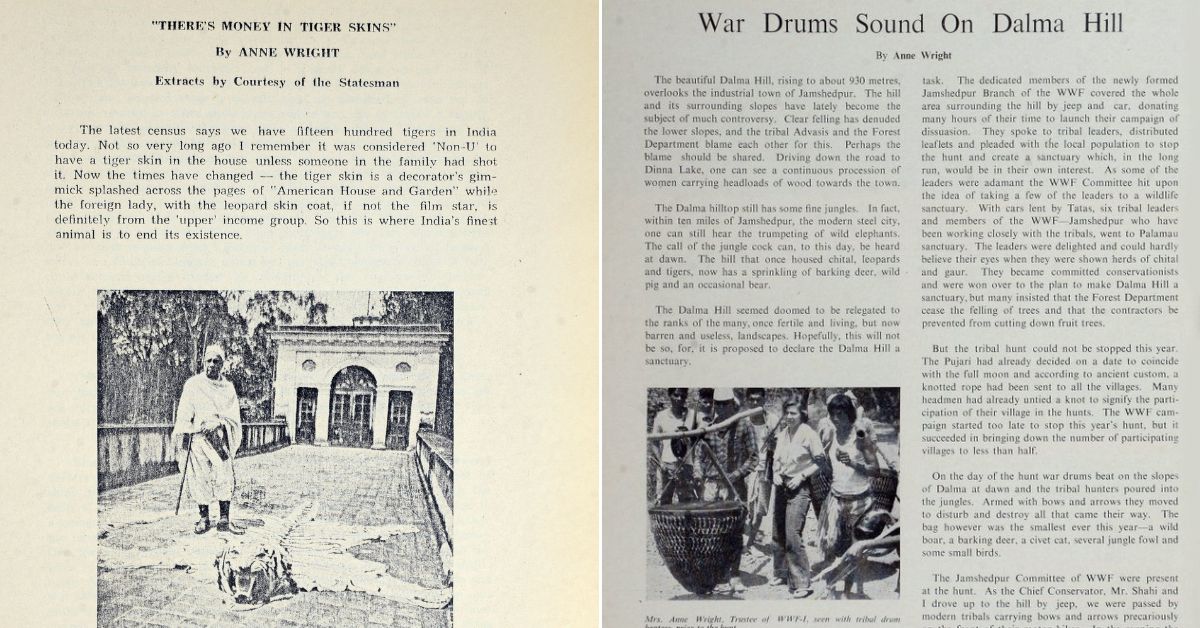

Her work, however, wasn’t just restricted to the forests of Palamau. She was also investigating the growing big cat skin trade in Kolkata. In 1970, she wrote an article published in The Statesman which describes in harrowing detail the illegal sale of tiger and leopard skins in Kolkata. The article was republished in The New York Times (NYT), causing a global storm.

As Raza notes, “The article was debated heavily in the Indian Parliament, and it isn’t an exaggeration to say that this article, along with the damning photographs on the scale of tiger hunting especially for skin trade, convinced the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi to ban tiger hunting the very same year (1970). That was the power of her pen.”

“It didn’t stop there. The global outcry in the aftermath of NYT republishing her article led to an outpouring of support for tiger conservation in India in terms of funds, resources and expertise. It culminated in the landmark ‘Operation Tiger’ that began in 1971 and eventually transformed into Project Tiger. Following the start of Operation Tiger, a task force of forest officers, conservationists and other eminent personalities was set up by the Indian government. Often known as India’s ‘First Tiger Task Force’, it was tasked with identifying areas for central funding and guidance for tiger conservation,” he adds.

The second such task force was formed in 2005 following reports in the media on the sudden disappearance of tigers from the Sariska Wildlife Reserve.

Anne was the only female member of this task force, and this is where she spoke vociferously about the inclusion of Palamau’s forests as one such area.

The fact that she had done so much groundwork in coordination with the concerned forest officers there now became a very important factor in helping her case for Palamau. Thus, eventually when the Task Force submitted its final report titled ‘Project Tiger’, Palamau was among the eight forests identified in the final report for central funding and handholding.

“This report then ushered in the Project Tiger scheme, and Palamau became one of the inaugural nine tiger reserves. Anne continued being involved in helping the tiger reserve management all through the 1970s, and by the early 1980s, Palamau was being ranked as one of the best-managed tiger reserves in the entire country. Besides Palamau, she also supported the cause for Similipal in Odisha, which also became a tiger reserve,” notes Raza.

Going further, she was also appointed by the Indian government to help draft the landmark Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972. Interestingly, according to Raza, she sourced a copy of the Kenyan Wildlife Act [from the Kenyan national polo team that had visited Kolkata to play a couple of matches], which alongside the Bombay Animals Act was among the two key legislative influences in the drafting of the final Wildlife (Protection) Act.

Helping establish other Protected Areas

“Without Anne, there would have been no Dalma Wildlife Sanctuary, a critical elephant habitat abutting Jamshedpur. She actively worked with the highest offices at the Union and State government levels to get it notified as a sanctuary in 1976,” says Raza.

Anne first visited Dalma soon after WWF came to India (WWF-India was founded in 1969). At the time, she was heading the Eastern Branch of the organisation. After her visit to these forests that lay adjacent to the famous steel city of Jamshedpur, she wrote an article for the WWF Newsletter in 1974 and began working to protect these forests.

By then, the Wildlife (Protection) Act had come into effect, and she lobbied hard with the Bihar forest department, the union government and the Tata Group, the standout private corporation in the area, to protect the forests of Dalma.

“She ensured that the plight of Dalma, its elephants, and wildlife, and the problem of unregulated customary hunting that was rapidly depleting the local fauna got enough press in Calcutta-based dailies as well as in WWF Newsletters and other publications. Meanwhile, funds for building basic infrastructure for wildlife management in these forests were arranged through the Tata Group, WWF, and other donors. Besides, she was also hard at work convincing the state government to provide financial support here as well,” notes Raza.

Similarly, she worked on mapping the best quality habitats that could be notified as a wildlife sanctuary with officers like SP Shahi and conservationists like Ashok Kumar, founder of the now well-known Wildlife Trust of India (WTI). She also launched a massive campaign to popularise Dalma among school students and Tata offices in Jamshedpur through the WWF.

“In addition, she lobbied hard for this forest in her meetings in Delhi as a member of the Indian Board for Wildlife, which was presided over by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. Eventually, two years after Anne first wrote about Dalma and began her efforts to secure this landscape, the forests of Dalma hills were notified as a wildlife sanctuary on 1 December 1976,” he adds.

Besides the Palamau Tiger Reserve and Dalma Wildlife Sanctuary, Anne was also responsible for the creation of other Protected Areas like the Balphakram National Park in Meghalaya (1986) and Neora Valley National Park in West Bengal (1986).

“Moreover, she cared deeply for the communities around the forest. In fact, her progression to becoming someone who dedicated her life towards wildlife conservation came in many ways because of her experience serving the remotest forest villages of Palamau during the Great Bihar Famine of 1967. Palamau was one of the epicentres of this famine. She camped for weeks at remote spartan forest bungalows like Kumandih (now lost) with her team from Calcutta providing relief for the starving masses by putting up open kitchens, water and food supplies, medical support, etc,” he says.

Anne served on the Indian Board for Wildlife for 19 years, besides the Wildlife Boards of seven states from Meghalaya to the Andamans. She also established the Rhino Foundation and supported numerous organisations involved in the conservation of the rhino including Aaranyak. Recognising her incredible service to wildlife conservation, she was awarded the Order of the Golden Ark in 1979 and the ‘Most Excellent Order of the British Empire’ (MBE) in 1983.

In 1982, she came back to the jungles of Kanha, where she grew up as a child, to establish Kipling [wildlife] Camp. She spent the last three years of her life in these forests with her daughter Belinda Wright, who herself has made incredible contributions to tiger and wildlife conservation in India, and according to Raza remains “Anne’s finest legacy”.

Legacy

Besides raising Belinda, Anne leaves behind an incredible legacy in just the incredible breadth and depth of her work. “This breadth is both temporal as she played an active role in the conservation of wildlife in India for more than 50 years and geographic since her active field conservation work spanned from Madhya Pradesh to the remote valleys of Meghalaya, the mangroves of Sunderbans, wilds of Odisha, rainforests of Andamans, and the forests of Chhattisgarh, the Chota Nagpur Plateau, and Terai,” says Raza.

And she was doing all this at a time when conservation, and especially field conservation, was almost entirely an exclusively male domain. In her younger days, she was working in forests that were hardly visited by any naturalist, much less anyone worrying about their conservation.

Her work could range from charting up a management plan for a single forest to working in framing a nationwide policy as she did during her years in the Tiger Task Force or as an important member involved in the framing of the Wildlife (Protection) Act.

“Moreover, what strikes out the most to me is her ability to forge alliances over common cause across an incredibly diverse set of people and stakeholders — from forest officers to politicians in high offices; from businessmen to communities living around forests; from celebrities and global and national public figures to young school kids; and from naturalists to policymakers. She worked with everyone and brought them together for the cause of conservation,” notes Raza.

“I can think of very few people, perhaps none, in India’s conservation history who single-handedly worked over such a long period, over so many states, and with so many diverse sets of peoples and interests in such harmony, and brought about such remarkable results. And of course who can forget the power of her pen,” he adds.

(Edited by Pranita Bhat; Images courtesy Raza Kazmi, Wildlife Protection Society of India (WPSI)/Facebook and Kipling Camp/Facebook)