After discussing the issues concerning Leh’s groundwater in Part 1, it’s time to highlight some of the actionable solutions available for the local administration, businesses, and residents. Addressing the gargantuan extraction of Leh’s groundwater and improving its quality will require a combination of modern solutions and leveraging traditional systems of water management.

Starting out, Dr Lobzang Chorol — who earlier this year completed her PhD from IIT-ISM, Dhanbad, after studying Leh’s groundwater systems for over six years — advocates for stricter regulation of groundwater extraction. While some of the measures she has listed below are already being implemented to some extent thanks to the Union Government-sponsored Jal Jeevan Mission, more needs to be done on war footing to ensure long-term results.

1. Mandatory permits: All individuals, businesses, and institutions should be required to obtain permits for drilling borewells and extracting groundwater. Permits should be granted based on a thorough assessment of the local groundwater resources and the sustainability of extraction. Authorities, including the Public Health and Engineering Department, must mandate a thorough site inspection before granting permissions for the construction of new borewells or septic tanks.

2. Metering of groundwater usage: The installation of water meters should be made compulsory for all groundwater extraction points. This will help monitor and regulate groundwater usage, ensuring that extraction remains within sustainable limits.

3. Pricing of groundwater: Introduce a pricing mechanism for groundwater usage to discourage excessive extraction and promote conservation. This can be in the form of a groundwater tax or a tiered pricing system based on consumption levels.

4. Zoning regulations: Implement strict zoning regulations to control the density of borewells and prevent over-extraction in critical groundwater recharge areas. This may involve establishing ‘no-go’ zones where groundwater extraction is prohibited or restricted.

5. Strict enforcement of waste disposal regulations: Implement stringent regulations on the disposal of solid waste, sewage, and industrial effluents to prevent contamination of groundwater. This should include mandatory treatment of waste before disposal, regular monitoring of disposal sites, and hefty fines for hotels and other businesses found dumping waste — including expired cement into water bodies. Moreover, clear guidelines must be set on the minimum distance that must be maintained between borewells and septic tanks, based on the local hydrogeological conditions and the potential risk of contamination.

6. Launch a public awareness campaign: To educate citizens about the importance of maintaining the proper distance between borewells and septic tanks, and the potential health risks associated with groundwater contamination.

7. Install water-efficient fixtures: Encourage hotels, guesthouses, and restaurants to install water-efficient fixtures, such as low-flow faucets, promote use of greywater recycling systems, and use treated water for non-potable purposes like irrigation and toilet flushing. They should also be mandated to undergo regular water audits, install rainwater harvesting systems, and receive financial incentives like tax cuts if they meet certain water conservation targets.

“To convince the industry to invest urgently, we need to emphasise both the environmental necessity and the potential for cost savings through efficient water use. Collaborating with eco-tourism certification programmes could provide an additional incentive,” she adds.

8. Regular monitoring and mapping of groundwater resources: Establish a comprehensive groundwater monitoring network and regularly map the groundwater resources to assess the impact of extraction and inform regulatory decisions. This is a particularly important concern given the lack of concrete data on the scale of groundwater extraction in Leh.

Speaking to The Better India, Dr Farooq Ahmed Dar — assistant professor at the Department of Geography and Disaster Management, University of Kashmir — agrees with this suggestion.

“Long-term monitoring programmes, measuring the trends in groundwater levels, identifying potential risks, and evaluating the effectiveness of conservation measures implemented in Ladakh from time to time are crucial steps that need to be taken,” he notes.

On the lack of concrete data, Dr Dar notes, “The major concern regarding the groundwater and its relationship with different environmental components is the lack of the data and understanding of its hydrodynamic processes. Understanding the systems, particularly the underground aquifers, is important. There is a crucial need to acquire data and gather accurate and reliable information on groundwater quantity, quality, and flow dynamics.”

“Modern tools and techniques like remote sensing, geophysics, tracers, etc are widely used to address groundwater problems. For this funding of research and development (R&D) projects is necessary. The effects of anthropogenic activities, such as population growth, urbanisation, and land use changes on groundwater resources need to be quantified. Integrating advanced modelling techniques can help in this direction,” he adds.

Radically improving Leh’s sewage treatment system

Regarding Leh’s wastewater treatment facilities, the current state is inadequate to meet the growing demands of the population and to ensure the safety of drinking water.

As Dr Chorol notes, “The existing facilities are ageing and lack the capacity to treat the increasing volume of wastewater generated in the city. Significant investments are required to upgrade and expand the water treatment infrastructure in Leh.”

One of these steps include upgrading the existing Sewage Treatment Plants (STPs) and constructing new ones in areas currently not covered by the sewage network. Authorities must also invest in advanced water treatment technologies, such as membrane filtration, to ensure treated water meets prescribed standards for safe consumption and environmental discharge.

“We also need to expand the sewage collection network to cover all households and establishments in Leh. Also, we need to establish a regular water quality monitoring programme to ensure that the treated water meets the prescribed standards and to promptly identify any potential contamination issues,” she says.

The exact investment required to take all these measures will depend on a detailed assessment of the current infrastructure and the projected future needs.

More importantly, however, Leh needs a decentralised sewage treatment plan. While a centralised sewage treatment plant would be ideal, it may indeed face significant obstacles given Leh’s mountainous terrain and scattered settlement pattern.

Speaking to The Better India, Dr Chorol says, “After further consideration, I believe a decentralised approach might be more suitable and practical for Leh.”

According to her, this includes:

1. Small-scale treatment systems: We could implement multiple smaller treatment facilities strategically located throughout Leh. These could serve clusters of households or neighbourhoods, reducing the need for extensive piping across difficult terrain.

2. Advanced septic systems: Promoting the use of modern, environmentally-friendly septic systems for individual households or small groups of homes could be effective. These systems can treat wastewater to a higher standard than traditional septic tanks.

3. Constructed wetlands: Where space allows, we could create artificial wetlands designed to naturally filter and treat wastewater. This eco-friendly approach could work well in some areas.

4. Dry toilets and composting systems: Given Leh’s water scarcity, expanding the use of waterless toilet systems could significantly reduce the volume of sewage produced. While constructing these toilets in the main town will be difficult given certain logistical constraints, hotels, guest houses, and homestays in villages should do more to encourage their use.

Implementation of these steps requires detailed mapping of Leh’s settlements and topography, serious and consistent community engagement, and collaboration with environmental engineers experienced in high-altitude and cold-climate sanitation. There should be a phased roll-out of each of these steps with pilot projects in key areas.

“This decentralised approach would be more adaptable to Leh’s unique geography and could be implemented more quickly and cost-effectively than a centralised system. It would also be more resilient, as a problem in one small system wouldn’t affect the entire area’s sanitation,” Dr Chorol says.

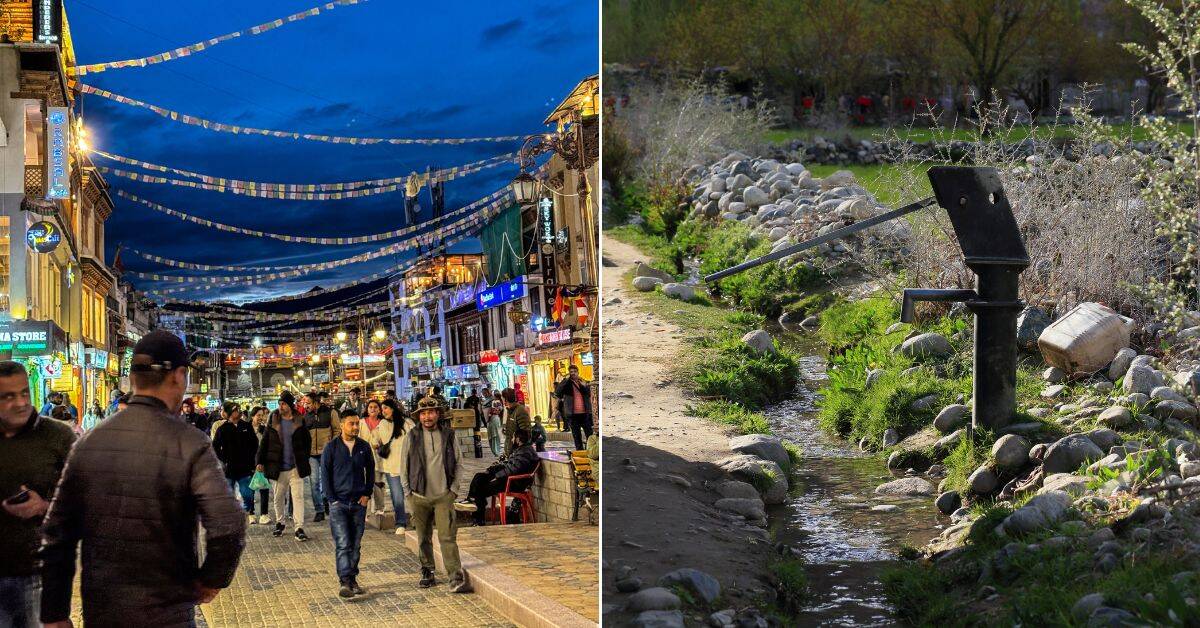

These steps are critical given how groundwater is primarily used by households, industries, hotels, and various institutions, particularly in the Leh town area.

Speaking to Mongabay, Dr Farooq Dar stated, “Whatever water is pumped from the underground reserves, roughly 93% of that is used for these purposes. Ladakh is also shifting towards self-sufficiency in the food and crop market.”

“This also demands huge [amounts of] water, and for that, people drill wells. The rest of the pumped groundwater is nearly 7%, used in crop fields, greenhouse vegetation cropping, fruits, and other crops not earlier grown in the region. Groundwater is also pumped by the hotel and guesthouse owners as they require fresh water for the tourists round the year,” he added.

Leveraging local knowledge

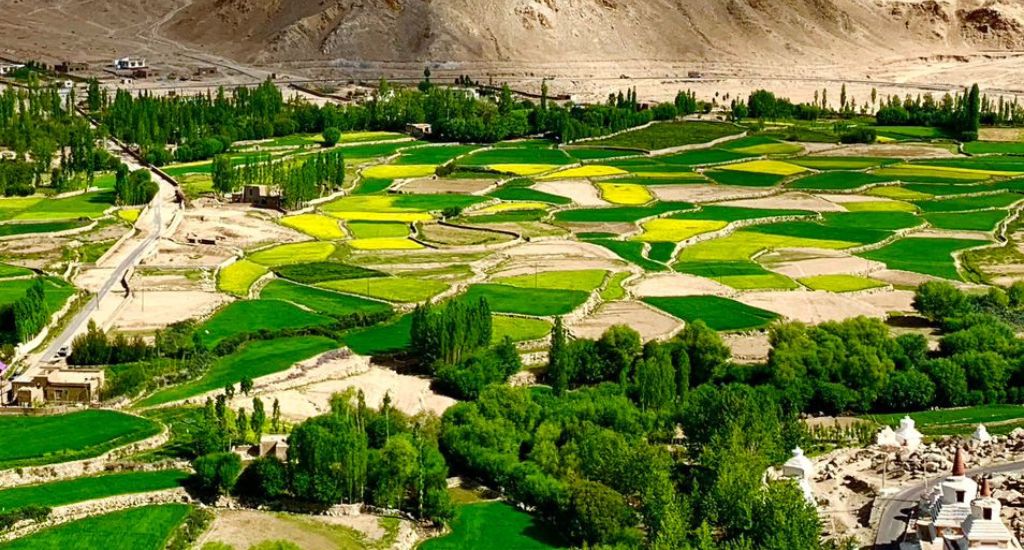

Given the growing dependence on groundwater in local agriculture for growing water-intensive crops, it’s necessary to hark back to traditional systems of water management.

As Dr Chorol notes, “The people of Ladakh have developed an incredibly sophisticated traditional ecological knowledge over generations of living in this harsh, high-altitude environment. Their intimate understanding of local hydrology, innovative irrigation techniques, and resource-efficient architectural designs are truly remarkable.”

“To elaborate on leveraging local knowledge systems for sustainable water use practices, we can draw valuable insights from traditional water management systems like those found in Ladakh. For instance, the Ladakhi system of appointing a chhur-pon or ‘water lord’ selected by villagers demonstrates how local communities can effectively govern their water resources. This model could be adapted to empower local water committees in other regions.”

But how does water traditionally flow in rural habitations?

In a 2006 paper titled ‘Traditional irrigation and water distribution system in Ladakh’ for Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge, authors Dorjey Angchuk and Premlata Singh explain, “The melted snow water from various rivulets, called kangs-chhu (ice water) merging at some point forms a togpo (stream) that flows through a valley touching many villages connected by the channel, called ma-yur (mother channel). It is built along a mountainside that forms its retaining wall, and is lined with clay to hold the water. This is termed the Ladakhi version of a dyke.”

“At some places rocks are broken to allow the passage of water or else where the rocks are too hard, a hollow poplar or willow trunk, called va-to is cut into two equal halves to allow the water easy passage. Water from the ma-yur is further diverted into yu-ra (small canals), which irrigates the fields. The point from where togpo water is diverted into ma-yur, and ma-yur water into yu-ra is called yurgo; and ska is the point from where yu-ra water is diverted to the field. Water in the ska is further guided through channels known as snang, which carry the water into the field.”

Meanwhile, the rotational water distribution system (bandabas) in Ladakh ensures fair allocation and could be studied and formalised in other areas to promote equitable water sharing.

How does it work? According to Dr Chorol, “The bandabas system is a traditional method of water allocation that has been practised in Ladakh for centuries.”

Here’s how it works on the ground:

- Villages are divided into sections, each with a designated water manager called a chhur-pon.

- Water from glacial streams is directed into a network of canals.

- Each section of the village is allocated water for irrigation on a rotational basis, typically for a set number of hours or days.

- The chhur-pon is responsible for opening and closing the water channels to ensure fair distribution.

- This rotation is usually determined by the size of land holdings, with larger farms receiving proportionally more water time.

- The system is flexible and can be adjusted based on seasonal water availability and crop needs.

- Community meetings are held to discuss and resolve any disputes or changes needed in the water allocation.

“Indigenous engineering techniques, such as Ladakh’s intricate canal systems (ma-yur, yu-ra), showcase local ingenuity in adapting to challenging terrains. By studying and applying such local engineering knowledge, we can develop context-appropriate irrigation solutions elsewhere,” explains Dr Chorol.

But how do these intricate canal systems work?

Ma-yur (mother canal):

- This is the main canal that diverts water from glacier-fed streams.

- It is typically built along contour lines to maintain a gentle slope for water flow.

- The ma-yur is often lined with stones to prevent seepage and erosion.

- It can stretch for several kilometres, bringing water to multiple villages.

Yu-ra (subsidiary canals):

- These are smaller channels that branch off from the ma-yur.

- Yu-ra distributes water to individual fields or clusters of fields.

- They are designed to follow the natural topography, minimising the need for pumping.

- Farmers use simple gates or stones to control water flow into their fields.

These systems allow locals to adapt to challenging terrains by:

- Utilising gravity for water distribution, reducing the need for energy-intensive pumping.

- Maximising the use of limited water resources in an arid environment.

- Preventing soil erosion through careful canal placement and construction.

- Allowing cultivation on steep hillsides through terrace farming.

Meanwhile, traditional water storage methods, like the use of ponds (rdzing) in Ladakh, can be revived and improved to enhance water security in water-scarce regions, notes Dr Chorol.

“Individual families rarely construct their own pond. Every year at the beginning of spit (spring), ponds are cleared of silts. Villagers collectively undertake the cleaning operation,” notes Dorjey.

But to develop and implement context-appropriate irrigation systems based on these principles, certain steps have to be taken, argues Dr Chorol:

- Conduct thorough site assessments to understand local topography, water sources, and soil conditions.

- Engage with local communities to incorporate traditional knowledge and practices.

- Design main canals that follow natural contours and use local materials for construction.

- Implement a network of smaller distribution channels that can be easily managed by farmers.

- Incorporate simple, low-tech water control structures that can be operated and maintained locally.

- Promote drought-resistant crops and water-efficient farming techniques suitable for the local climate.

- Establish community-based management systems for equitable water distribution and system maintenance.

“Also, integrating customary rules and practices, like Ladakh’s sa-ka ceremony before the first watering of the field, can increase community buy-in for water conservation efforts. The deep ecological knowledge of local farmers, such as understanding soil moisture (ser) and optimal irrigation timing, can be tapped to improve irrigation efficiency. Respecting local spiritual connections, like the belief in water deities (lhu), can promote conservation ethics,” she notes.

“The sa-ka ceremony can increase buy-in for water conservation efforts by reinforcing the cultural and spiritual significance of water, encouraging respectful use. It also encourages intergenerational knowledge transfer about traditional water management, promotes shared responsibility for water resources, and creates a sense of ownership,” she adds.

Finally, participatory monitoring approaches, inspired by the surveillance role of the chhur-pon and community members in Ladakh’s water distribution system, can ensure effective local oversight of water resources. Any effective water conservation strategy in Leh has to start by first recognising and empowering these local knowledge systems.

“This means thoroughly documenting and studying these practices to understand their underlying principles and effectiveness. Then, we need to find ways to incorporate them into contemporary water management plans and policies. Importantly, we have to establish platforms for knowledge-sharing and co-learning between local communities and external experts, and foster a spirit of collaboration. We must encourage local communities to maintain, revive, and innovate upon their traditional water management systems,” notes Dr Chorol.

“Most crucially, we have to ensure that local voices and perspectives are central to the decision-making process when it comes to water resource allocation and conservation efforts. The path to a water-secure future in Leh lies in striking a balance between modern scientific knowledge and the wisdom embedded in traditional ecological knowledge systems,” she adds.

(Edited by Pranita Bhat; Images courtesy Dr Lobzang Chorol, Shutterstock, X/Sahilinfra2, Village Square)