Have you ever sampled a plate of gupchup shami kababs? Don’t fret if the answer is ‘no’. Loosely translating to ‘kababs with a secret’, they were a creation of the household in Bhopal where heritage activist and storyteller Sikander Malik grew up. He feasted on them on the regular. Sikander credits ‘Abba’, his landlord, for these exquisite luncheons.

As his essay ‘The Lost Kitchen Cabinet of Bhopal’ divulges, Abba inherited the recipe for the gupchup shami kababs from his freedom fighter father Rafiq Ahmed. As Sikander writes, such was his love for the dish, that the sound of the grinder alone — indicating that ‘Amma’ (the landlord’s wife) had commenced the preparation of the kabab paste — would make his ears perk. He’d sprint to her kitchen, fully willing to devour the paste as is.

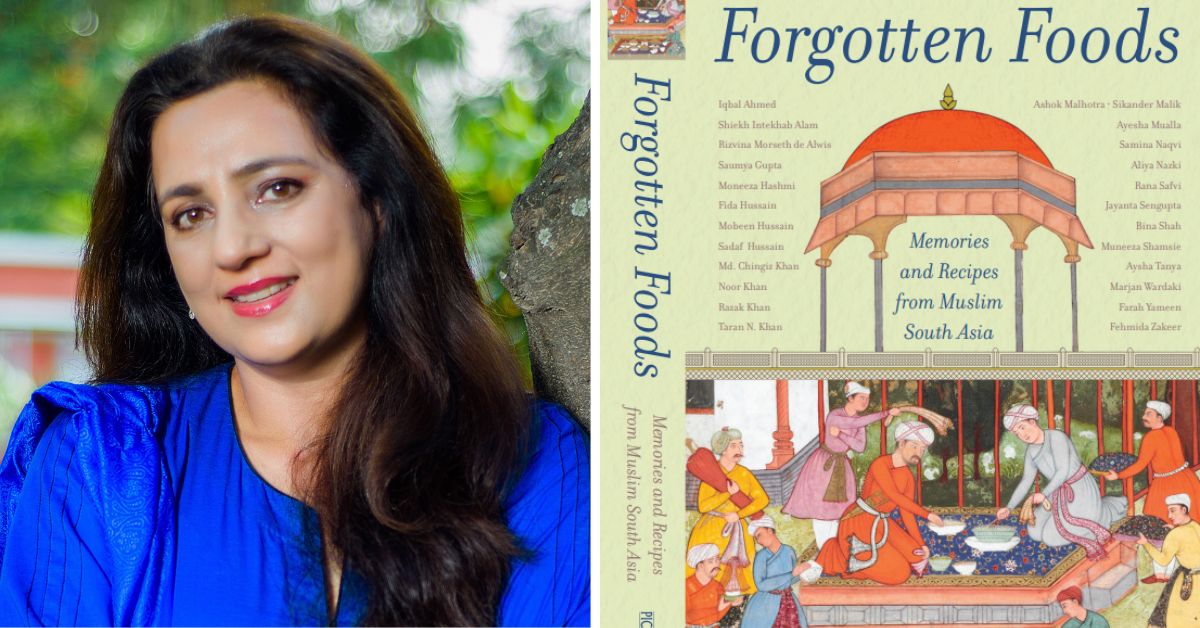

To know how that story ended you’ll have to get your hands on the anthology Forgotten Foods (2023), which, along with Sikander’s antics, features recipes of historic South Asian dishes and culinary traditions shared by virtuosos across the subcontinent.

The Better India chats with cultural historian Dr Tarana Husain Khan, who has co-edited this literary work of art along with Siobhan Lambert-Hurley, professor of global history at the University of Sheffield and Claire Chambers, professor of global literature at the University of York.

Resuscitating forgotten foods through narratives

Celebrating the quiet artistry of home cooking, Forgotten Foods marks just one triumph in Tarana’s diverse culinary journey. Previously, she authored the critically acclaimed Degh to Dastarkhwan: Qissas and Recipes from Rampur (2022) and won the Kalinga Literary Award for her historical fiction The Begum and the Dastan (2021).

A firm believer that serendipity often makes for the best stories — and recipes, Tarana shares the role fate played in her journey, recalling a chance visit to the Rampur Raza Library years ago. This, she says, marked an inflection point of her induction into food history. “I had a chance encounter with a cataloguer who led me to the Persian cookbook manuscripts. When I got my hands on the 19th-century manuscripts, I was stunned at the nearly 300 recipes recorded there,” she shares.

As she would discover, these were variations of pulaos (pot rice dish), kababs (minced meat cooked on skewers), qormas (meat braised in thick sauce), and sweets cooked in Rampur.

The more she learnt about South Asian cuisine — from studying the manuscripts and conversing with veteran culinary geniuses in the years that followed — the more she was saddened how delicacies that were once commonplace in South Asian kitchens had become shadowed by contemporary alternatives.

This sparked the idea of Forgotten Foods, an attempt to ensure these dishes are not obliterated from history altogether. In many ways, the anthology is a coming together of historians, scholars, plant scientists, heritage practitioners, writers, and chefs — attempting to do due diligence by South Asian cuisine.

One of the contributors is Sikander Malik. In his essay, Sikander articulates his love for the gupchup shami kababs made out of minced qeema (meat) instead of meat pieces “or the long-cut parchas primarily used for pasandas”. As for what lent the kababs their tenderness, he writes, it was the kachumber, the recipe of which he divulges in the book.

While Forgotten Foods celebrates this meat feast, it also takes pride in the Bihari kababs, which, for MasterChef India finalist (2016) and chef consultant Sadaf Hussain, were synonymous with Eid festivities back home in Bihar when he was younger. He would watch, amused, as his Abbi sliced the meat in thin sections, mixed it in the marinade, skewed and laid it on the sigdi (grill).

While the modern-day kababs have lost touch with these traditional versions, Tarana discovered some dishes that have stayed true to their roots. For instance, the Yarkhandi pulao.

Documenting changing food habits across geographies

It was at a nondescript food stall in Ladakh where JNU (Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi) PhD scholar, Fida Husain’s aunt Ama Haji would get her fill of Yarkhandi pulao. In her essay, Fida writes that the Yarkandi polla reflects the cultural heritage of Ladakh as a confluence of cultures. “Made the traditional way — slow-cooked in a heavy stone pot called a doltok in Ladakhi — the dish was said to be symbolic of the big hearts (read: deep pockets) of the hosts for their guests. This bounty was proven by the amount of fat/ghee dripping down one’s elbows while eating.”

Fun fact: Ladakh was a stranger to rice, the protagonist of the dish, until about seven decades ago. It was improved transport links and connectivity that transformed the once luxury item into a staple of the Ladakhi diet.

While in the Northeast, local sensibilities dictated recipes, in Central and Eastern India, it was royal customs that did. This is what Tarana discovered during her stay at Bhopal’s Jehan Numa Palace Hotel — which belongs to the descendants of Nawab Sultan Jahan Begum’s second son, Nawab Muhammad Obaidullah Khan, and is known for its preservation of heirloom recipes of Bhopal’s Nawabi cuisine. Here, she enjoyed a front-row seat to two dishes with a rich history: the Bhopali rezala (chicken cooked with spinach) — which she learnt, amalgamates the local flavours with Awadhi and Mughal cuisine and is popular in West Bengal — and the filfora (a unique mincemeat preparation).

Sharing more about these, she says, “Bhopalis apparently prepared rezala from peacock meat until hunting peacocks was banned. As for filfora, it has its roots in the hunting traditions of Bhopal. Upon the killing of an animal – usually nilgai, deer or gazelle – its meat was coarsely chopped or sliced into slivers while still warm, and immediately fried with some basic ingredients on a campfire.”

This made for a rustic meal for the hunters. The modern version of the filfora includes hand-chopped mincemeat cooked with ginger–garlic paste, turmeric, chillies, onions, yoghurt and coriander.

As the book takes its course, we’re taken on a winding journey across the subcontinent. From qiwami seviyan (whose recipe Karachi-based writer Muneeza Shamsie chanced upon after her mother’s passing) and winter staple sarson ka saag (shared by Moneeza Hashmi, daughter of the legendary poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz) to historian Rana Safvi’s lahsan mirch ki chutney and digital archivist Farah Yameen’s kaleji fry, amidst others — each chapter conjures an image of the pomp and splendour the dish enjoyed in its heyday.

With each recipe, the hope is that these dishes may once more find a way back into our kitchens.

Edited by Pranita Bhat